What can valuations reveal about the worth of intangible assets?

Are sectors growing or shrinking? IAs help see beyond the headlines

How do you value something that can’t be seen? What sort of metrics can be used to gauge things that often don’t even appear within any financial reports?

These are the kinds of questions that plague anyone tasked with the daunting job of valuing a company’s intangible assets. Those assets exist – the company wouldn’t be operating if they were an illusion – but the trick is not just in locating them, it’s in finding ways to value them that don’t end up sounding like, well, an illusion.

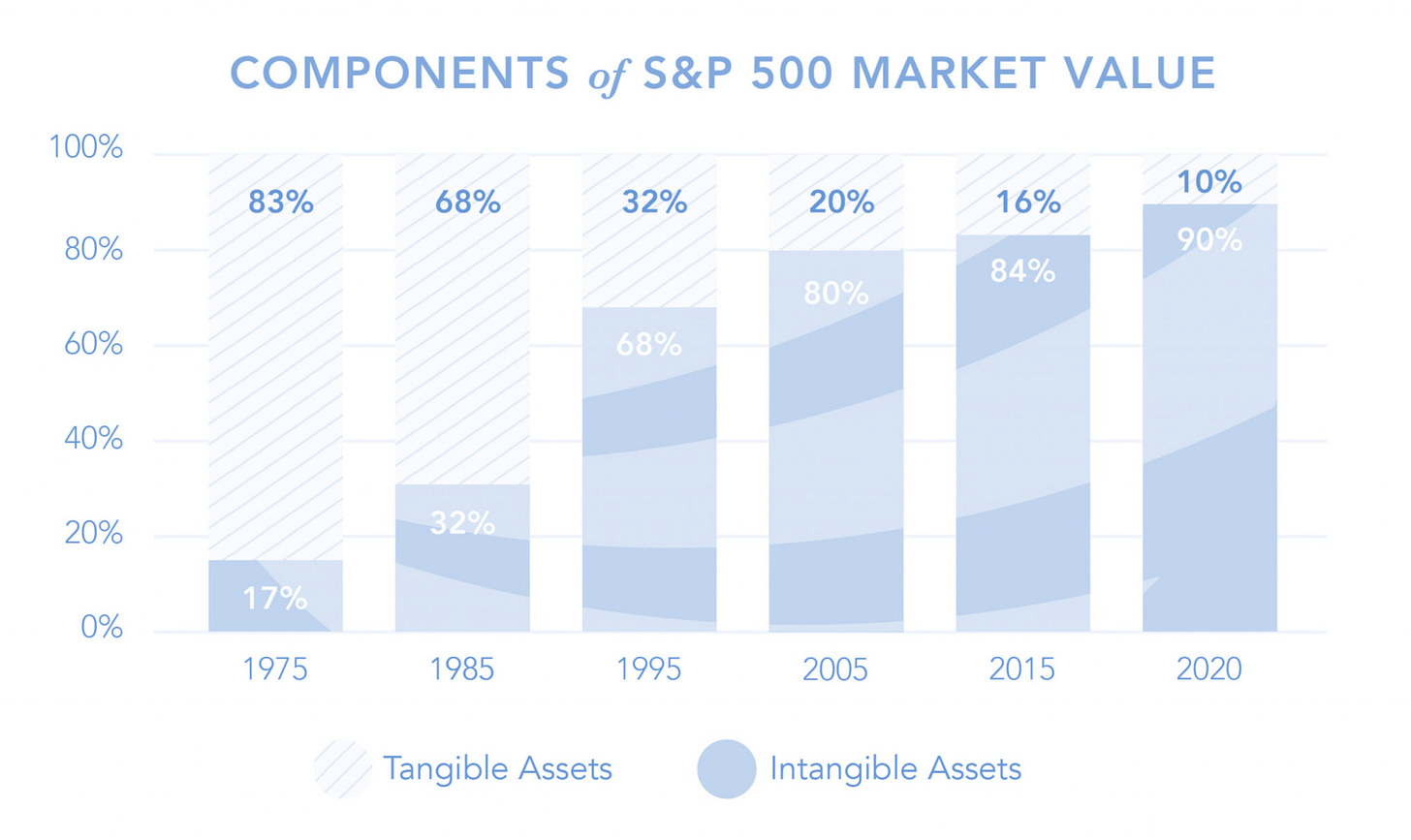

One of the first firms to have a crack at estimating the value of intangible assets en masse was the Chicago-based Ocean Tomo merchant bank. Its research showed the incredible flip of company value between 1975 to 2020 in favour of intangibles and away from tangible assets.

As Ocean Tomo pointed out, in 1975 more than 90% of the average company’s value was in tangible assets – things like factories, land, property, ships or rail. As the world entered the so-called “Information Era,” it was intangible assets (like data, content, software, patents, etc) that suddenly became much more valuable. By 2020, 90% of the average company value was intangible.

You can read Ocean Tomo’s report here.

The method Ocean Tomo uses to measure this is to look at market value. The method has many angles of attack, depending on the type of asset being valued.

For example, a Comparable Company Analysis (CCA) and Comparable Transaction Analysis (CTA) involve comparing financial metrics to those of similar companies or recent transactions, since they reasonably assume similar businesses should have similar valuations. Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis estimates the present value of a company's expected future cash flows, incorporating forecasts, discount rates, and present value calculations.

Earnings multiples, such as the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, assess a company's value relative to its earnings, providing insights into investor expectations. Asset-based valuation considers the market value of a company's assets, useful for businesses with significant tangible assets. Finally, book value, derived from a company's balance sheet, represents the difference between total assets and liabilities. They’re full of boring mathematics, but each of these approaches works pretty well.

Valuation is part science and part art. This is because economic conditions, industry trends and investor sentiment tend to influence market valuations. None of these are perfectly knowable with data and experiments, which is why valuation can sound like an art. Ocean Tomo chooses to use the market value valuation technique, but this can leave a lot of value undisclosed, especially for intangibles.

Another way to perform the tough job of intangible asset valuation might be to follow the path of Deloitte who this month launched a report using an enterprise valuation (EV) method instead. You can read this new report here.

Deloitte is relatively new to the intangible asset valuation game. As one of the largest analyst firms on the planet (part of the Big Four), of course, Deloitte was already dealing with intangibles. But clearly, it sees the importance that intangibles now play in boosting company value.

Deloitte’s marketing collateral doesn’t go into great detail about how its team will go about valuing a client’s intangible assets, but its decision to use an EV valuation method instead of market value is intriguing because it’s not the first consulting firm to do this.

And Deloitte was not the first to do this. The specialist firm EverEdge Global also saw a problem in strictly looking at the market value of a company to judge the worth of its intangibles and undertook its own research into the value of intangible assets as a proportion of enterprise value back in 2021. It researched the S&P 500, ASX 200, NZX All Index and FTSE ST All Share indices. You can read EverEdge’s report here.

Specialising in intangible assets since well before it became vogue, EverEdge has plenty of experience in applying different types of valuation methods to identify the worth of tangible and intangible assets held by an organisation.

That both EverEdge and Deloitte decided independently to use enterprise value valuation is an important factor. Especially because it lets us see if this method has consistent results over time, and if those results reflect observable reality.

Before we tackle that question, however, here’s a quick run-down on how an EV valuation works.

EV valuations are meant to provide a full picture of a company's worth by considering not only the market value of its outstanding shares (market capitalisation) but also its debt, minority interests and preferred equity. By including debt in the valuation, EV offers more nuance about a company's financial health. Such valuations are useful when comparing companies in the same industry.

In other words, EV is often a better choice for valuation purposes because it has a more comprehensive understanding of what a business really is.

So, what can we learn from the results of the Deloitte and EverEdge reports? How do they reveal the way the world’s intangible asset landscape may be changing?

Back in 2020 (which EverEdge used as its data set), EverEdge assessed the ratio of intangible to tangible assets in six different sectors in the ASX. A lot of these sectors are analogous in each report since Deloitte also looked at the ASX.

Here’s the breakdown from EverEdge:

· TMT – 77%

· Healthcare – 93%

· Consumer Goods – 76%

· Industrials – 81%

The Deloitte report shows some movement in the analogous categories. For example:

· TMT – 83%

· Healthcare – 86%

· Consumer Goods – 75%

· Industrials – 79%

Given that Deloitte and EverEdge were presumably using the same or similar EV valuation methods to attain their results, along with the same companies on the ASX, the ratio movements over the last three years are curious.

In the first instance, we have TMT (technology, media, telecom) making a giant jump in its net intangible value, rising 6% overall during this period. That makes sense given the increased digitisation of all businesses operating in this sector, a trend which will likely continue for the foreseeable future. It’s probably a bit unfair to lump so many different industries under the same category as “TMT,” but these are the stats we were given.

On the other hand, the ratio of intangible to tangible assets in the healthcare sector surprisingly dropped 7% across the three years. At a first approximation, it’s unclear why this would be the case given that healthcare is surely subject to many of the same digitisation forces as the TMT sector. In non-pandemic times, the bulk of medicine can likely be delivered telephonically, with more options moving online for patients all the time.

But stepping back a bit, the Covid-19 pandemic may have forced healthcare companies to invest more heavily in tangible assets to cope with the surge in medical emergencies. If that’s true, then barring another random outbreak of a major disease, the healthcare sector should return to a wider trend of digitisation soon.

Both the categories of Consumer Goods and Industrials stayed relatively stable during this period, dropping by only 1% and by 2%, respectively. This could reflect a ceiling for intangibles in these sectors, whereby most of the low-hanging fruit of digitisation has already been plucked. Perhaps there isn’t much more value that can shift from tangible to intangible. It will be interesting to see if the ratio hovers near the same rate or if it logs more significant jumps as people figure out ways to add more intangible value to these sectors.

Unfortunately, the two reports aren’t directly analogous. Nevertheless, they do offer a high-level view of how intangible assets are taking over the business world.