Intuitively, we all understand that products and services have some value. After all, a homeowner must pay a plumber to fix their pipes, they won’t just turn up for free.

But what about intangible assets that are neither products nor services? Is something only valuable if a customer wants to buy it?

Consider a note written by an executive at Coca-Cola to another executive referring to a new Coke flavour that hasn’t yet appeared on shelves. Could the information – the intangible asset – contained on that sheet of paper be worth millions of dollars?

In the spring of 2006, one woman bet her career, reputation and future on exactly this assumption.

It was Monday, 12 June at 7:30 PM. Long after her colleagues had left for the evening, Joya Williams finally stood up from her desk and grabbed her bag to leave. But instead of heading out the door, she walked over to a handful of important-looking filing cabinets and began thumbing through the documents contained inside.

Williams’ day job was as an administrative assistant for a marketing director at Coca-Cola, so handling such documents was hardly outside her normal parameters. Except this time her goal wasn’t to “administer” the documents. Instead, she removed a few folders and placed them inside her bag. She also stuffed a specific container of liquid in the bag with the papers. Williams then departed Coca-Cola’s headquarters and drove home with the precious cargo.

Are Trade Secrets Valuable?

At this point in the story, how much do you think her bag was worth?

If a bank robber stops to count the stolen cash in a safe, he will immediately know how much the loot is worth. And while an art thief may have some trouble deciphering the value of a famous painting, he can assume that rich people will pay top dollar no matter what.

But the value of a stolen sample of soda and a few files is entirely unknowable until a buyer is in the room. It could be worth millions, or nothing at all.

To Pepsi, a can of classic Coke is worthless since Pepsi has plenty of soda already. But a small container of an unreleased Coca-Cola prototype might be gold dust to Pepsi.

Pepsi could test that sample to discover what’s in it. It could improve the formula and be the first to market with a superior drink. Pepsi could even prepare attack advertising in advance of the release of Coke’s new product to kill the rival’s momentum before it gets rolling. Practically speaking, the benefits of seeing a rival’s trade secrets are limitless.

Let’s take a brief pause to define what trade secrets are.

Trade secrets are pieces of proprietary information owned by a company that hold crucial significance for the organisation but do not meet the specific criteria for patent protection. These might include recipes, business processes, specialised formulas or any number of other types of information.

Protecting these intangible assets requires a strategic approach. The key is to maintain strict confidentiality and ensure every employee, from top to bottom, signs a Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) to shield against any unauthorised disclosure. In certain jurisdictions, a breach of an NDA is a criminal offence, reinforcing the gravity of maintaining utmost secrecy.

But back to the heist story.

Williams had access to executive-level materials as well. These contained detailed information about suppliers, strategies, hidden bottlenecks and consumer data. It's difficult to overstate the value of such material for Pepsi. Coke gathers data and washes it through analysis to optimise its systems.

Coke knows which shelves in shopping centres are best to book, how to get in front of a target demographic, which areas of a city it should focus on, when to release new advertising campaigns to achieve the greatest impact, how to break into a new market, what associations people make with drinking Coke and thousands of other little insights.

Arguably this data would be more valuable to a rival like Pepsi than Coke’s recipe. And Williams was gathering more of it every day.

Williams broadly understood the value of her stolen material to Pepsi but didn’t know the exact worth or how to facilitate selling it. So, she recruited a friend who could help fill those gaps: Edmund Duhaney, recently released from prison for drug trafficking. Duhaney then recruited one of his prison buddies, Ibrahim Dimson, who’d done time for bank fraud and embezzlement.

According to court testimony, the three met for the first time at Williams’ apartment on 4 April of the same year. Williams prefaced her devious plan for corporate espionage by saying, “This happens all the time in corporate America” before mentioning that “Pepsi would be interested in this type of information.” Everyone knew just how much those two companies hated each other. So surely Pepsi would pay top dollar for the stolen info?

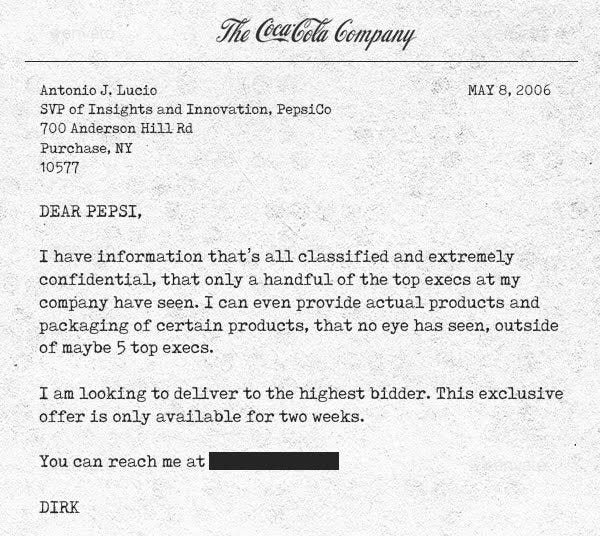

The following month, they were ready to put the plan into motion. Using an official Coca-Cola letterhead (why?), Ibrahim penned a note to Pepsi headquarters under the fake name “Dirk.” The message began in earnest: “Dear Pepsi, I have information that's all Classified and extremely confidential that only a handful of the top execs at my company have seen,” he wrote.

At this point, the three still had no idea what Pepsi might pay for the information, so they asked for a measly $75,000 which, I suppose, was a large amount for a few ex-felons and a lowly corporate secretary.

How (Not) To Perform Price Discovery

Determining the value of intangible assets is difficult for the experts, let alone a few poorly-prepared sandlot criminals. Williams, Dimson and Duhaney had limited options available, aside from trial-and-error, to gauge just how much money they could get from Pepsi.

Following a ham-fisted negotiation between the criminals and Pepsi, on 16 June two men – “Dirk” (Ibrahim) and a man presumably from Pepsi called “Jerry” – travelled separately to a clandestine meeting at Hartsfield-Jackson International in Atlanta, the world’s busiest airport.

Ibrahim arrived clutching a brown Armani Exchange bag. Inside the bag was a manila envelope containing a clutch of documents labelled “highly confidential,” along with the sample of the unreleased soda developed by Coca-Cola.

The other secret squirrel attendee, “Jerry” from Pepsi, must’ve stuck out like a sore thumb in the airport crowd. He walked past the commuters with a yellow Girl Scout cookie box, packed with $30,000 (40% of the agreed-upon sum, with the rest to be exchanged after Pepsi could confirm the sample was legitimate).

Dirk and Jerry exchanged their bags and went on their way.

It turned out the secrets were valuable after all! And this was just the beginning. Williams had since stolen more product samples, memos and even a presentation meant for the International Olympic Committee.

Over the next several months, Jerry from Pepsi would meet with Dirk, pay some money and get Coke’s trade secrets. In June, Jerry agreed to pay $1.5 million for the balance of the stolen material. That’s million! With an “M”! The criminal trio were riding high – until it all went wrong.

What Are Trade Secrets Worth

It turned out the three ne’er-do-wells were talking with Special Agent Gerald “Gerry” Reichard of the FBI all along. Back when Ibrahim sent the first letter claiming to be a Coke employee, Pepsi had sent the note straight over to Coca-Cola with a warning that there was clearly a mole in the company leaking trade secrets for money. Coke immediately contacted the FBI.

Little did the criminal trio know, all the money they were getting was from the Feds. Oh, and Coke also installed cameras by Williams’ office to monitor everything she did while she was in the building. The FBI would eventually have plenty of videos depicting each time she snuck those confidential documents into her bag. The case was pretty much open and shut.

All three were charged with conspiracy to commit theft of trade secrets, which are federal offences. Ibrahim Dimson pleaded guilty and received five years. Edmund Duhaney entered into a plea agreement to testify against Williams in exchange for just two years behind bars. And Williams was sentenced to eight years in prison.

When the accomplices appealed these sentences, the Eleventh Circuit jury “attached great weight to one factor: the seriousness of the offence.” The case summary went on:

In describing why it found the offence to be so serious, the court discussed the harm that Coca-Cola could have suffered if Williams and her co-conspirators had succeeded in selling its trade secrets to a rival, and the danger to the US economy these crimes pose.

Everybody seemed to agree with the severity of the punishment. As the market becomes more global, US Attorney David Nahmias wrote of the case, “the need to protect intellectual property becomes even more vital to protecting American companies and our economic growth.”

In response to the incident, Coca-Cola strengthened its security protocols and took steps to enhance the protection of its trade secrets. Overall, the case served as a great example of the legal consequences and potential damage that can arise from the theft of valuable proprietary information.

Valuable Trade Secrets

Coca-Cola already went to enormous lengths to protect its intangible assets, so it certainly thought they were valuable. As noted in Atlanta Magazine:

Like everyone hired at Coke, Williams went through a tough screening process – including a physical exam – and experienced tight security as part of her day-to-day routine at a company that takes its safekeeping seriously. Most visitors are required to park several blocks away and ride a shuttle to the building. Surveillance cameras are stationed in the public parts of the headquarters[.]

Clearly, Coke’s internal communications, data and IP could be worth something to rivals. But when that information literally landed on the front doorstep at Pepsi’s HQ, it seems the only thing Pepsi figured was worth more than the secrets was avoiding the lawsuits and PR blowback that would result from being involved in corporate espionage.

On the other hand, maybe Coke’s secrets were never all that valuable to Pepsi.

When you consider that Pepsi's very existence is almost entirely defined by its rivalry with Coke, this would make sense. As mentioned above, Pepsi spends billions every year marketing not just its own soft drink, but also the fact that it is different from Coke. The thieves didn’t really think through if Pepsi could even use its rival’s secrets.

So, what was the value of Coke’s secrets?

Only one person in this story assigned an actual cost to the stolen goods.

Judge J. Owen Forrester gave no quarter to Williams’ tearful begging at her Federal District Court hearing. Sentencing guidelines suggested somewhere between five and six years would be an appropriate punishment for the crimes, but he took a different view.

“The guidelines as they are written don’t begin to approach the seriousness of this case. This is the kind of offence that cannot be tolerated in our society,” Judge Forrester told the court.

So, that’s your answer. For Joya Williams, those intangible assets were worth eight years in prison. Not exactly a good ROI…